Going short in 1608

Buying a stock, or taking a ‘long position’ in financial jargon, is what you do when you expect the price of that stock to go up. If, on the other hand, you expect the price of a stock to go down, you can take a ‘short position’. This can be done by borrowing stocks from a third party and then selling these. When the price indeed goes down, you can buy the stocks back at a lower price before returning them to the lender, and thus make a profit. Nowadays, this is an everyday activity for many stock traders, made easy by the services of brokerage firms. Remarkably, it was also daily practice in early 17th-century Amsterdam, even after Isaac le Maire had made short selling infamous, and the States-General of the Dutch Republic subsequently banned the practice.

Isaac le Maire

Isaac le Maire was originally from Tournai in modern-day Belgium. Like many other merchants from the Southern Netherlands, he migrated to the Dutch Republic in the late 16th century and settled in Amsterdam. He was a very wealthy man. After having been involved in one of the first Dutch expeditions to the East Indies, he became a co-founder of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in 1602. He wouldn’t be on the board of directors for long, however. On February 22, 1605, he stepped down after coming into conflict with his colleagues over a mundane matter of money. He signed a declaration that he would never again be involved in an enterprise, in the Dutch Republic or abroad, that traded beyond the Cape of Good Hope or the Straits of Magellan—the then known sea routes from Europe to Asia.

Le Maire, however, was not so easily put aside. He would devote the rest of his life to thwarting the business of the VOC. One of the ways he did this was by trying to bring the share price down. He started this in 1608. It was an early example of shareholder activism—he believed the company was making wrong decisions and if the directors would not listen to him, he had to make his beliefs clear in some other way. But it was also just a way of making money. Because what Le Maire did, was organize a ‘bear raid’. He founded a syndicate with nine other men: Hans Bouwer, Cornelis Ackersloot, Cornelis van Foreest, Willem Brasser, Jan Hendricksz Rotgans, Jacques Damman, Maerten de Meijere, Haermen Rosecrans, and Steven Gerritsz. They agreed to sell VOC shares for future delivery—shares they did not own, or at least not yet. They were taking a short position.

This put downward pressure on the share price, which Le Maire and the others tried to amplify by spreading rumors about the company on the bridge and in the chapel where the shares were traded. It was smart of le Maire to do this with a number of accomplices. After all, he was well known in Amsterdam. Everyone was aware of his difficulties with the directors, so they would have seen straight through his plan. By using the syndicate, people really believed that the VOC was in bad shape. It went as expected: the price went down. And when it did Le Maire and his clique sold more shares for future delivery, at an even lower price. This served to reinforce the negative sentiment among the traders.

Forward contracts

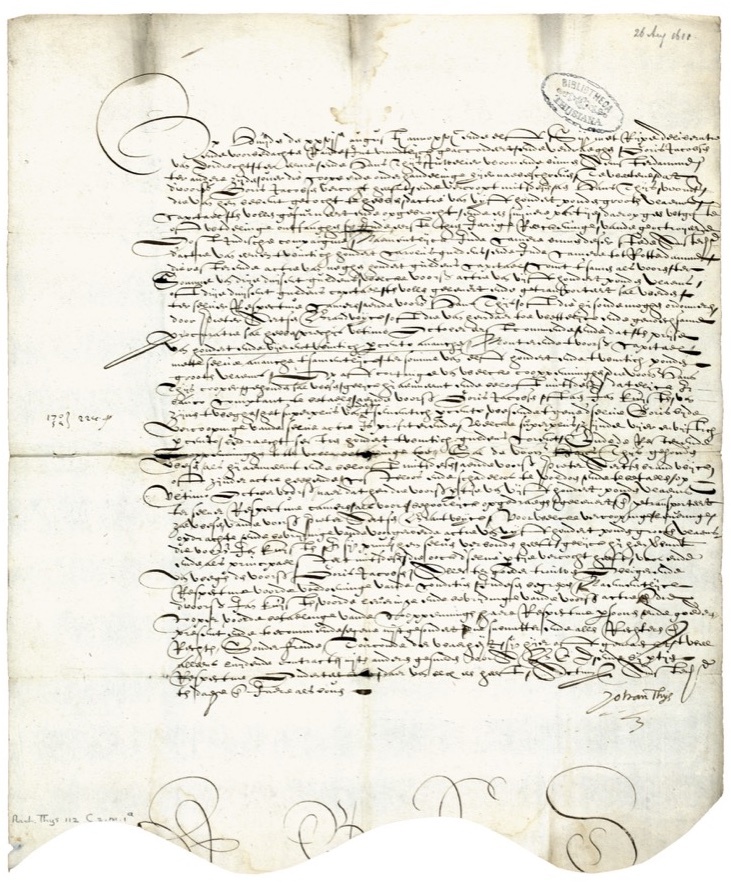

Le Maire and his syndicate used forward contracts for their bear raid. Selling borrowed shares would also have been an option, but was more difficult to organize, all the more because it would have involved frequent visits to the VOC bookkeeper (in this blog post I explain how title to a share was transferred). Trading forwards was comparatively easy. Merchants were used to this kind of contract from the grain trade. All it took to strike a forward deal, was a written contract—it was not customary to ask for collateral.

Thysius Archive, inv. no. 112 C2, doc. no. 1A. Bibliotheca Thysiana, University Library, Leiden.

These forward deals were agreements that established that the parties would trade a VOC share at a particular time in the future at a price set at the moment that the transaction was entered into. They are comparable to modern-day futures contracts, but where futures are standardized contracts, each forward was negotiated individually. Forward trading was convenient to share dealers. No share was transferred, and there was no need to pay anything at the time the contract was signed. None of this happened until the contract’s end date. And even then it was not necessary to transfer the share. Traders could opt for a cash settlement, in which case they would offset the price in the contract against the spot price at that moment—the price at which shares were changing hands on Nieuwe Brug.

A ban on naked short selling…

Somehow the directors of the Amsterdam branch of the Dutch East India Company got wind of what Isaac le Maire and his syndicate were up to. They took immediate steps to counter it, possibly because Le Maire was behind it, but it was also very much in their interests that the share price did not drop too much, because they each owned a substantial amount of share capital. Their first act was to submit petitions to the highest administrative bodies in the Dutch Republic. They wrote that they had recently found out that “vile practices” were being widely employed in the buying and selling of shares. They explained exactly what was happening without naming Isaac le Maire or his accomplices and asserted that this was all “very disadvantageous to the investors and particularly the many widows and orphans.” The directors’ reasoning was that many widows and orphans were dependent on their VOC share for their income. This yield had become negative as a result of le Maire’s actions.

In fact, the number of widows and orphans who were dependent on an investment in the company was very small, but playing on their painful situation pricked the puritanical conscience of the authorities. This worked out: counter-petitions of (anonymous) shareholders did not sort any effect with the authorities. On February 27, 1610, a month after the last petition had been sent, an edict banning practices such as that of Isaac le Maire and his syndicate was promulgated—the first stock market regulation in the history of the world. It was a ban on naked short selling, or “blank selling”, as it was then called in the Netherlands: blank sellers sold shares for future delivery while their accounts in the company’s share register were empty. Borrowing a share from a shareholder and selling it on the market (short selling) would still have been allowed.

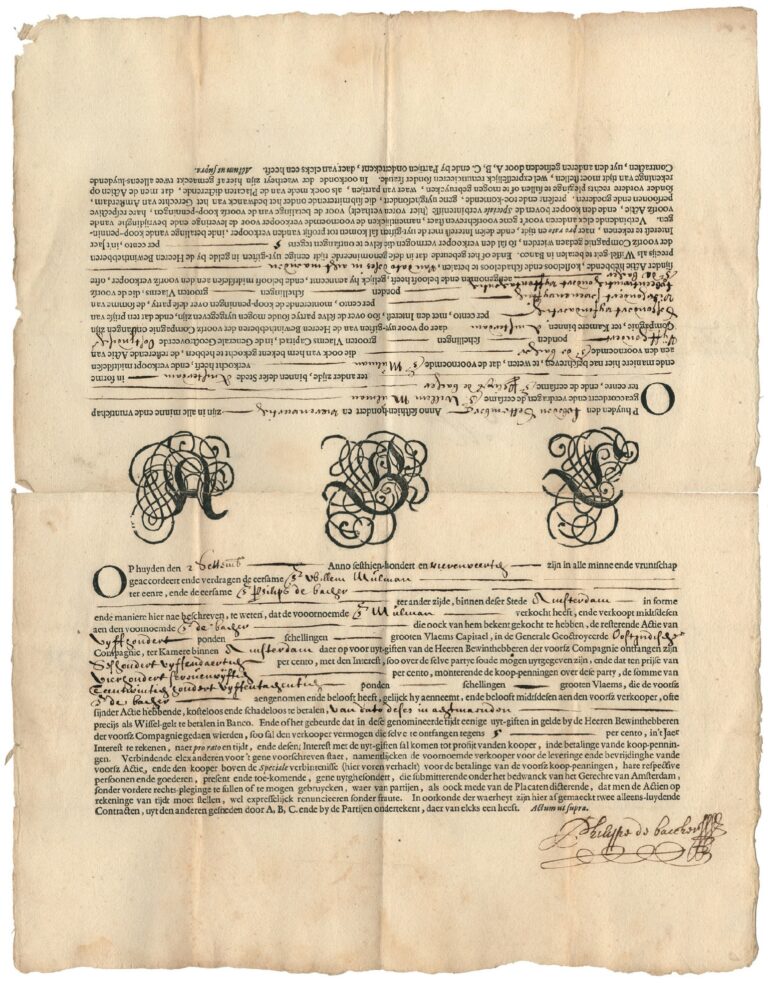

…that was widely ignored

The States-General of the Dutch Republic re-issued the ban on naked short selling in 1623 and a few more times later. It is clear why they considered this necessary: the ban was widely ignored. The main effect of the ban had been that traders now always included an additional clause to their forward contracts. The clause stated that both parties to the contract declared that they would only go the Amsterdam aldermen’s court to enforce delivery of or payment for the share. They waived in advance any other legal procedure or a lawsuit for other reasons. They also declared that while they were familiar with the content of the rules governing forward trading, they explicitly decided to take no notice of them.

National Archives, The Hague. Collection of civil case documents from the Archives of the Supreme Court of Holland, inv. no. IIB274.

The share dealers could use such contracts. The 17th-century derivatives market was fully self-organized. There was no exchange commission that set the rules. The authorities could only exert indirect influence. What regulated the market, was a set of unwritten rules, underpinned by each trader’s dependence of his good reputation: the dealers adhered to the unwritten rules, otherwise they could no longer do business on the stock exchange.

The end of Isaac le Maire

The ban on naked short selling was not an immediate threat to the transactions of Isaac le Maire and his bear syndicate because it did not come into effect until two months after the promulgation, in other words, at the end of April 1610. But the whole episode ended badly for them anyway. Once the plans of Isaac le Maire and his fellow bear traders were known, the share price no longer went down. The short sellers tried to settle as many transactions as possible as quickly as they could—with very little success, however, because many of the counterparties preferred to wait until the expiry date of their contracts in the hope that the share price would rise. For Isaac le Maire there was an additional problem: the VOC had blocked his account in the share register, which made it impossible for him to buy shares and use these to settle his forward deals. He relocated to the town of Egmond aan den Hoef, 40 kilometers north of Amsterdam. Here Le Maire did not encounter the share dealers every day, and the notaries and court bailiffs who wanted to remind him of his obligations would have a harder time finding him.

Isaac le Maire’s troubles did not keep him from trying to thwart the business of the VOC, however. In 1614, he founded the ‘Australian Company’ in the town of Hoorn. The aim of this company was to find a new route to the East Indies, a route that was not covered by the Dutch monopoly on trade with Asia, granted to the VOC by the Dutch States-General in 1602. The expedition that left the Netherlands in 1615, led by Isaac le Maire’s son Jacob, did indeed find a new route: it was the first European expedition to sail through Le Maire Strait and round Cape Horn, named after Hoorn, the Dutch town where their company was based. However, in the interest of the VOC, Dutch judged ruled that the claim of Le Maire’s company to be allowed to trade spices was unfounded. Le Maire died on 20 September 1624. The inscription on his gravestone in Buurkerk in Egmond-Binnen tells us that although he lost 1.5 million guilders during his foreign trade activities over a period of thirty years, he had kept his honor.

NPR Planet Money

In 2015, financial podcast and blog Planet Money, produced by American National Public Radio, made an episode on Isaac le Maire’s bear raid. It features an interview with me.

Planet Money later also made a short video about Isaac le Maire and his efforts to bring the VOC share price down. You can view it here.

The Planet Money team asked me in the interview for their podcast on Isaac le Maire how traders negotiated their deals. I answered that Joseph de la Vega’s famous book Confusión de confusiones (1688) about the Amsterdam stock exchange suggests that this involved a physical process called ‘handjeklap’ in Dutch: traders make offers and counter-offers, and each offer is accompanied by a blow to the other trader’s hand. The traders’ dance at the end of the Planet Money video is a free interpretation of this process. ‘Handjeklap’ is occasionally still practiced in the Netherlands, mainly by livestock dealers. The video fragment on the right (click to view on YouTube) shows how it’s done. The footage comes from the 1963 documentary ‘The Human Dutch’ by Bert Haanstra.