The oldest share

The VOC was the world’s first company whose shares were actively traded. It would therefore make sense that the world’s oldest share certificates had been issued by the VOC. It is not quite like that, however.

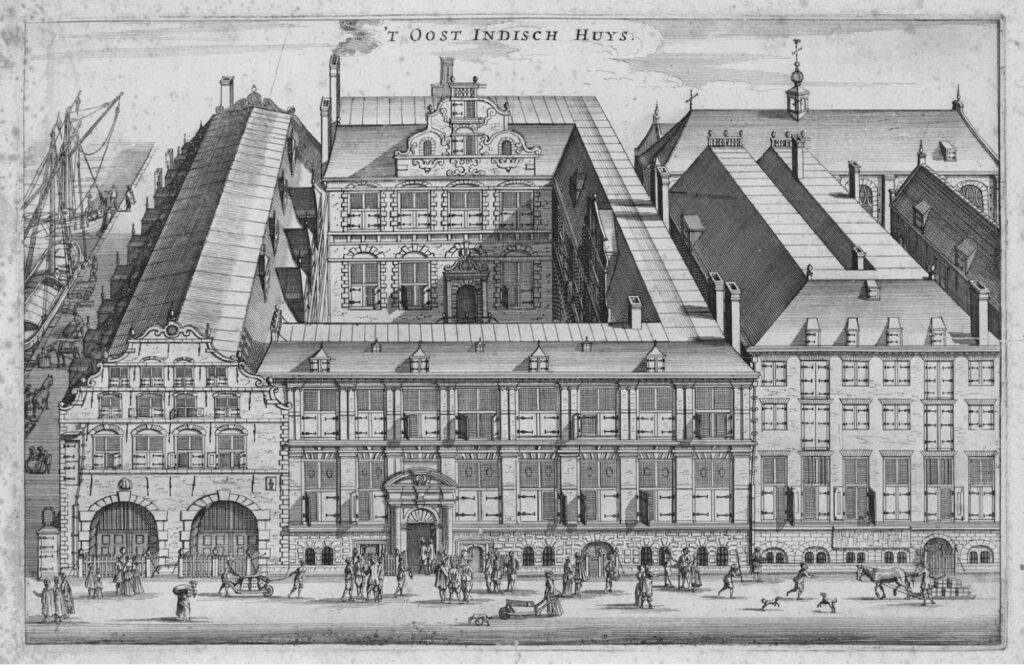

The VOC charter of March 1602 stated that the company would issue registered shares. Subsequently, the introduction to the capital subscription ledger of August 1602 explained the procedure for transferring the ownership of a share. (Read more about these documents and the IPO of the Dutch East India Company in this blog post.) When two share traders had struck a deal, the buyer and the seller (or their authorized representatives) had to appear together before the company bookkeeper, and two directors had to approve the transfer before it became official.

Stadsarchief Amsterdam. License: CC0.

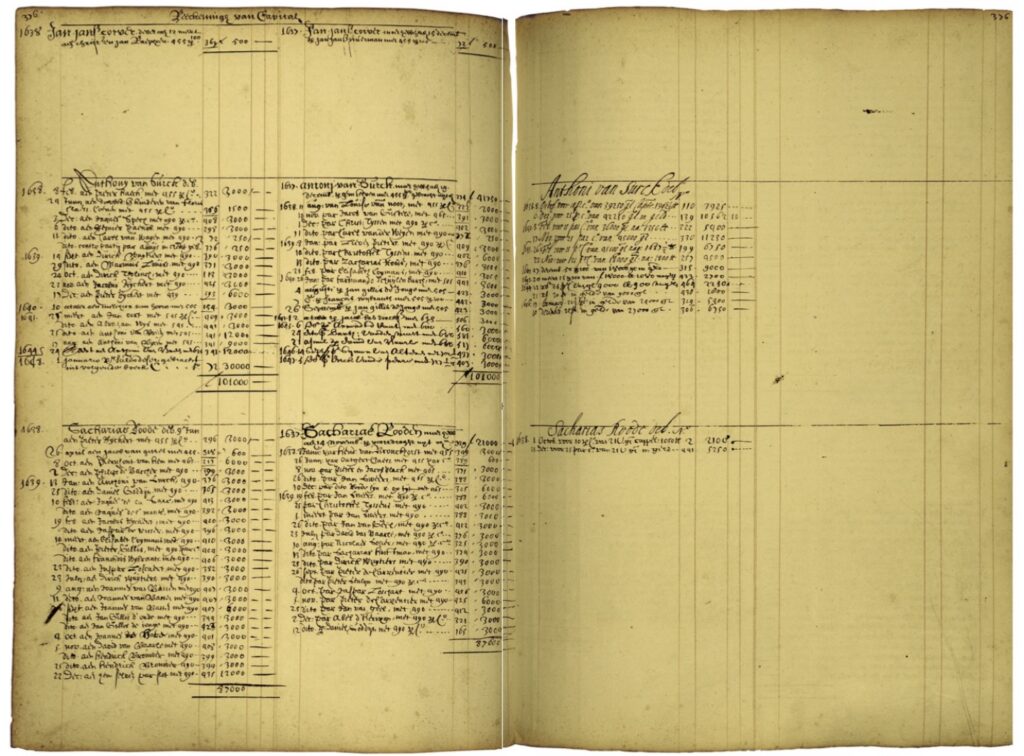

An account for every shareholder

The bookkeeper kept a large ledger in which every shareholder had an account. If a shareholder sold a share, his or her account was debited by the amount concerned. And if he or she bought a share, the account was credited. (This system is comparable to the way in which banks currently maintain statements for their account holders.)

National Archives, The Hague, VOC Archives, inv. nr. 7068, fo. 376.

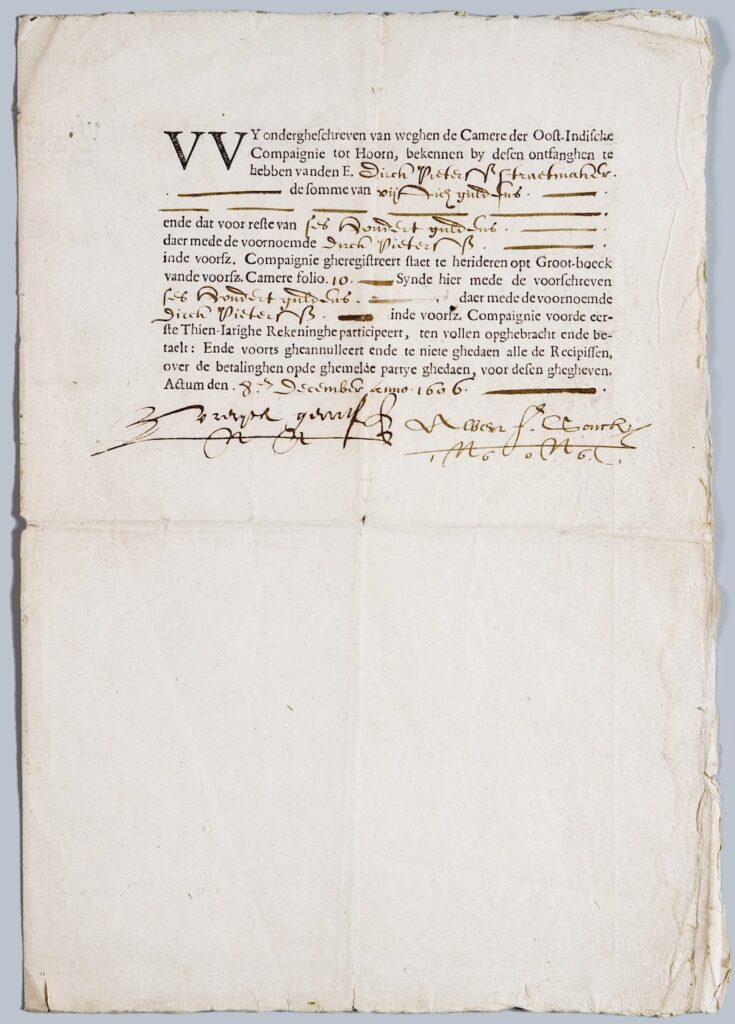

These administrative steps were necessary because the VOC did not issue bearer shares. Shareholders themselves had no written proof that they owned a share in the company. Investors who had subscribed to the company’s IPO in 1602 did, however, receive a receipt when they had paid up the last installment of their subscription. The document shown below is the receipt dated December 8, 1606, for the remaining fifty guilders for a share of 600 guilders in the Hoorn branch, paid by Dirck Pietersz Straetmaker.

Collection of the Capital Amsterdam Foundation, Amsterdam.

The worlds oldest ‘shares’

These documents are often called the world’s oldest shares. Just four of these documents have survived until today. The Amsterdam ‘share’ dated September 27, 1606, which was probably stolen from the Amsterdam City Archives during the 1980s and played a starring role in the movie Ocean’s Twelve, is the receipt for the last 400 guilders of a total investment of 4,800 guilders by Agneta Kocx. The share currently belongs to a group of German investors, who in 2004 announced that they were prepared to sell it for the astronomical sum of six million euros. The oldest one is dated September 9, 1606. It was found in 2010 in the Westfries Archief in Hoorn.

Practical receipts

It was convenient for Dirck Pietersz Straetmaker and other shareholders that the folio numbers of their accounts in the VOC ledger were recorded on their receipts. It made it quick and easy to trace their accounts when they went to the company’s office to transfer a share or collect a dividend payment. And perhaps the bookkeeper also regarded the receipt as a proof of identity. The same is probably true for the transcripts from the transaction book that the buyer of share received from the bookkeeper after ownership had been transferred to him.

The receipts and transcripts were also practical for administrative purposes. They often contain notes on dividends. But they could not trade their receipts, which were certainly not valid proof that they owned shares in the VOC. The text of the receipt makes this plain. The recipients of such documents were recorded in the ledger as owners of shares. Only a positive balance in the ledger of the company’s capital accounts was valid proof of ownership of a share.

Related post

Many traders preferred trading derivatives over the spot market, partly probably because they wanted to avoid the time-consuming trip to the bookkeeper and the transaction costs that an official transfer involved. Read more about the derivatives trade in my blog post on Isaac le Maire and his attempt in 1608 to bring the price of VOC stock down by taking a large short position.